SELWYN COLLEGE

1882 – 1973

A Short History

The Master, Fellow and Scholars

Selwyn College, Cambridge. 1973

George Augustus Selwyn was the first Bishop of New Zealand 1841-68, and at the end of his life, Bishop of Lichfield (1868-78). He helped to create not only the Church in, but also the Dominion of New Zealand; a big, powerful, controversial, fearless man. His work in New Zealand and his personality created an extraordinary impression among the Victorians. He was one of the great men of his generation. Charles Kingsley expressed what many people felt when, in his dedication of Westward Ho! (1855) he paid tribute to George Augustus Selwyn, and Rajah Brooke of Sarawak, as "pure and heroic" examples of the highest type of English virtue. The name 'Selwyn College' first occurs as a suggestion made very soon after his death on 11 April 1878, in a committee to consider how he might suitably be remembered.

At the place of honour in the College Hall hangs a beautiful portrait by George Richmond, painted in 1855. This portrait, of a deeply spiritual and very determined man, was painted for St John's College where Selwyn was an undergraduate (he rowed in the first Cambridge crew to race against Oxford in 1829) and later a Fellow. St John's College gave it to Selwyn College in 1969. In the New Senior Combination Room stands a less beautiful bust of a no less determined old man, by Armstead, bequeathed by Selwyn's widow in 1907.

The Selwyn Memorial Committee had as secretary Charles John Abraham, who had been suffragan bishop to Selwyn both in New Zealand and afterwards at Lichfield. No one did more to drive the Committee in the direction of a college, encourage it when it flagged, continue the quest for money when money began to fail, and design the earliest stages of the foundation. Though Selwyn has no 'founder', Bishop Abraham has more claim than any other to be regarded as the author of its being. The College has a bronze bust of him in the New Senior Combination Room.

Abraham and the other founders had clear objects in their minds. They wanted an ordinary college, not a theological college; a college to educate everyone, not simply a college to educate future clergymen. But George Augustus Selwyn was identified with the missionary drive of Christian Churches towards the new wide world of the nineteenth century. The college therefore should make provision for those who intended to serve as missionaries overseas. It should also make provision to educate the sons of clergymen. These were the two aims stated explicitly in the Charter of Foundation.

Selwyn himself had wished to see university education extended to many who were not able to afford it. The founders saw the expense of Victorian Oxford and Cambridge, and were ahead of their time in wanting to enable poorer students to attend. In those days there were no grants from public money, and few scholarships from private endowment. They determined therefore that living should be inexpensive. They wished also that the College should be as Christian in its tradition as befitted the memorial to a great bishop. When they issued an appeal for money, they laid it down that "the distinctive features of the proposed college would be that is should be founded on the broad but definite basis of the Church of England, neither less nor more; and further, that its aim should be to encourage habits of simple living, and to develop the Christian character in its students".

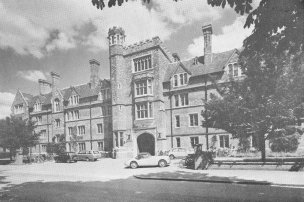

In 1879 the founders elected a Master (10 March), decided to invite the Archbishop of Canterbury to accept the office of Visitor (28 June), and bought (3 November) from Corpus Christi College six acres of farm land bordering on Grange Road (cost £6,111.9s7d). The site afforded matter for argument, for they could have gone to a cramped site in the centre of the town on Lensfield Road (where now stands the Roman Catholic Church), and some feared that on Grange Road the College would look too far out of the centre to feel, or be felt, an integral part of the university. Luckily the argument for space won the day. Soon afterwards they chose an architect, Mr (afterwards Sir Arthur) Blomfield. Building began in 1880. The corner-stone on the north side of the gateway was laid by the Earl of Powis on 1 June 1881 in the presence of the Vice-Chancellor and numerous dignitaries including the American ambassador and thirteen bishops. The College was opened in time for the October term 1882.

In 1879 the founders elected a Master (10 March), decided to invite the Archbishop of Canterbury to accept the office of Visitor (28 June), and bought (3 November) from Corpus Christi College six acres of farm land bordering on Grange Road (cost £6,111.9s7d). The site afforded matter for argument, for they could have gone to a cramped site in the centre of the town on Lensfield Road (where now stands the Roman Catholic Church), and some feared that on Grange Road the College would look too far out of the centre to feel, or be felt, an integral part of the university. Luckily the argument for space won the day. Soon afterwards they chose an architect, Mr (afterwards Sir Arthur) Blomfield. Building began in 1880. The corner-stone on the north side of the gateway was laid by the Earl of Powis on 1 June 1881 in the presence of the Vice-Chancellor and numerous dignitaries including the American ambassador and thirteen bishops. The College was opened in time for the October term 1882.

The Memorial Committee petitioned the Queen for a Charter of Incorporation, which was granted on 13 September 1882. The Charter provided (among much else) for the government of the College by a Master and Council of 16 members, five of whom were ex-officio. The Charter made no provision for Fellowships, and this omission later gave rise to difficulty.

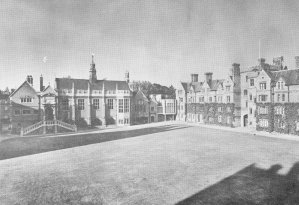

When the first undergraduates (28 of them) arrived in October 1882 they saw the west side with gate and tower and staircases A and B much as they are now. The College kitchen was there more or less as it stands underneath the present Hall and capable of bearing a not-yet-built Hall on top. About twenty feet from A and B staircases, and parallel to them, ran a long temporary and functional building of a single storey in which were the Chapel, the Hall and Buttery. Everything else was waste land and piles of earth. The undergraduates lived on B staircase, because the Master and his family lived in ten sets of rooms on A staircase, and the tutor lived up the Tower over the gateway. The lavatories were earth closets, and did not become water closets until 1913. The baths were tin baths in rooms, and there were no modern baths until the bath-house was built behind the Hall in 1927. The lights were oil lamps for undergraduates, gas for dons; electricity being installed during 1923. The Library, a meagre collection of books, was housed in what is now the Tower Room over the gateway. The Master had no kitchen on A, and his family fed off the College kitchen. Across Grange Road were only fields, with no trees. Sidgwick Avenue did not yet exist, and the kitchen back quarters reached outward to touch the back quarters of Newnham College across a narrow lane. (Sidgwick Avenue was built in 1893; the College encouraged it, and was glad to surrender land). The teaching staff consisted of the Master, the tutor and one non-resident lecturer. They were afterwards amazed at how many different subjects they taught.

The first Junior Combination Room was in the temporary building on the grass, opposite the gate. For a time it was on the ground floor of D staircase, later (1935) in what is now a conference room at the foot of C staircase but was originally a lecture room. The College debating society ran the Junior Combination Room, and meetings were sometimes not sure whether they were meetings for business or meetings for debate. The first recorded motion (29 October 1883) disapproved "further operations in the matter of the Channel Tunnel". In the first two or three years the junior members of the College abolished horse-racing by law; disapproved the government; refused to extend the franchise to unmarried women; refused to abolish competitive examinations; advocated higher wages for the labourer; disapproved tipping; considered smoking "morally and intellectually beneficial"; deplored the Deceased wife's Sisters' Bill, and carried a motion against compulsory Chapel, but refused to carry the motion that "lectures are a farce" or to abolish Proctors. Almost from the first there was a Music Society. The tradition of Selwyn music, which in the middle twentieth century was to become one of the well-known features of the College, started early, though we do find the Master protesting at an early meeting of the Society against those who "pelt the performers and interpolate choruses", apparently because the music was thought to be too classical and severe.

The first Master was Arthur Lyttelton, who had the experience of a tutorship at Keble College in Oxford, and the merit that he came of a family eminent in Church and State. His mother was sister to the wife of the Liberal Prime Minister, Mr Gladstone, and he was himself a supporter of the Liberal party in politics. He persuaded Gladstone to make a personal gift to the College of the louder of our two Chapel bells, for Gladstone evidently thought that undergraduates needed to be well woken if they were to get up by times in the morning.

To get the new College accepted in the university, and accepted by the university as a college, was not going to be easy. The other colleges of Oxford and Cambridge were foundations of the Church of England, and only twelve years before must have none but members of the Church of England on their governing bodies. In 1871 Gladstone passed an act which opened the governing bodies to men of any religion or none, and some fifteen years before that another government had allowed undergraduates of any religion or none. When Selwyn College was founded, nothing in the Charter said that only members of the Church of England should be admitted. But Lyttelton issued a notice that none but members of the Church of England would normally be admitted. This caused some in the University to think that to found Selwyn was an attempt to put the clock back. They expected its heads and guides to be conservative if not reactionary. It was no small strength to the College that its first Master should be so evidently no reactionary in politics and so easily able to call the mighty Gladstone to his aid. Lyttelton was a sensible and godly man, and Cambridge University rapidly accepted him and Selwyn, in part because of him.

The opposition was more vexatious than formidable. A few men wrote letters to the Cambridge Review or made speeches in the Senate House. The most pertinacious of these critics was the celebrated Oscar Browning of King's College. But to be attacked by Oscar Browning was not always a disadvantage. And other members of the University were warm in their welcome for the young and struggling College.

Lyttelton's difficulties were many. He could only take twenty freshmen in 1883 because there was room for no more, and a college of only 48 men was not viable. Hence he got himself out of A staircase by building himself the Master's Lodge (1883-4). The house was built for thirteen maids, who slept up what is now G staircase, which was carved out of the Master's Lodge in 1934 to make rooms for undergraduates and fellows. C and D staircases were ready for October 1884, E and F staircases for 1889. At the front of the College there was nothing until a straggly hedge grew, not replaced by the low wall (architect T H Lyon) until 1939.

It was one object of the foundation to keep the fees as low as was consistent with good management. All undergraduates paid £27 a term to cover costs of food, lodging, lectures and tuition, with a small surcharge if they studied medicine, natural sciences, or engineering. But the difficulty of managing was great. They kept down the cost of wages by making a large use of apprentice College servants.

It was a bad time for higher education. Other colleges in Cambridge, even ancient colleges, felt the pinch of poverty. Cavendish College, founded the same year as Selwyn, soon went bankrupt and had to close down. Another near-contemporary, Ayerst, also closed. To survive at all, in that economic climate, was a feat.

The feat could not have been performed without the willingness of the teaching staff to receive less than reasonable pay. "It's success" wrote F S Marsh "was wholly due to the self-sacrificing generosity of men who must always be honoured as among the greatest benefactors of the College. These were a succession of young, and often brilliant scholars, who, because they believed whole-heartedly in all that Selwyn represented, were willing to share its life as tutors, lecturers and teachers in return for a microscopic stipend and the knowledge that they had helped a worthy cause".

Their classes may have consisted of others besides intellectuals. No Selwyn undergraduate was placed in the first class of the Classical tripos until fifteen years after the foundation, and then it was W H S Jones, afterwards the famous authority on disease in the ancient world, and Fellow of St Catherine's College. Progress was slow on several fronts, but it was always progress. In rowing, the Selwyn crews startled everyone by the speed with which so many new and diminutive a college raced up the river.

One other difficulty faced the first Master, and not only the first. The world persisted in thinking of it as a college for training future clergymen, not as an ordinary college for training anyone. This was in part because so many of its first undergraduates sought holy orders. Out of the twenty of the first 28 undergraduates whose careers are easily trackable, fifteen were ordained (75%). Of those who took the BA degree between the foundation and 1901, 237 took orders, 90 became schoolmasters, 29 doctors, 16 lawyers, 12 soldiers, and 5 civil servants. For a long time members of the College needed to deny to the uninformed that they were a college for educating clergymen. In 1969 the number of undergraduates who were ordained, amid the cooler breezes of the modern world, was down to approximately 3%. But it is safe to say that a large percentage of its undergraduates have become Christian ministers in every year since 1882 than those of any other college in Cambridge.

In the New Senior Combination Room hangs a portrait of Lyttelton by C W Furse, doubtless the finest portrait in the College after the Richmond portrait of Selwyn. In 1893 he returned to parochial work, soon to die of cancer at the age of 51. He left the College full, and behind him the memory of a fine teacher and a reserved, aloof-seeming man of judgement, decision and piety. The Lyttelton Room, a public room at the foot of G staircase, was not called in his honour until 1935, when the room was panelled after a design by T H Lyon The stained glass window, third from the end of the south side of the Chapel, is a memorial to him.

In the New Senior Combination Room hangs a portrait of Lyttelton by C W Furse, doubtless the finest portrait in the College after the Richmond portrait of Selwyn. In 1893 he returned to parochial work, soon to die of cancer at the age of 51. He left the College full, and behind him the memory of a fine teacher and a reserved, aloof-seeming man of judgement, decision and piety. The Lyttelton Room, a public room at the foot of G staircase, was not called in his honour until 1935, when the room was panelled after a design by T H Lyon The stained glass window, third from the end of the south side of the Chapel, is a memorial to him.

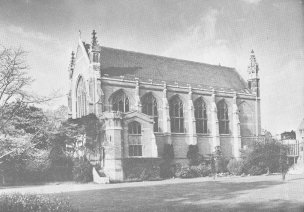

The Chapel

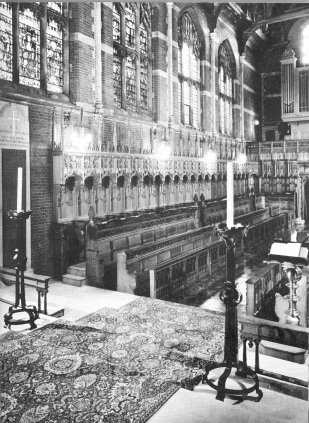

The Chapel and Hall within the Court were recognizably too temporary. It was characteristic of the founders that they sought to build a permanent Chapel before they sought to build a permanent Dining Hall. Sir Arthur Blomfield was invited to prepare plans in June 1892, building began in spring 1893, the corner-stone was laid by Bishop Abraham on 15 June 1893 (which was Lyttelton's last day as Master), and the Chapel was consecrated on St Etheldreda's day (17 October 1895), by Archbishop Benson of Canterbury. By then the stalls were completed as seats, and included the impish carved heads of Lord Morley, Lord Salisbury, Sir William Harcourt, and other politicians prominent in the general election of 1895. But the stalls each side had no carved canopies above them, the windows had no stained glass, and the organ and sanctuary were 'temporary'.

The Chapel and Hall within the Court were recognizably too temporary. It was characteristic of the founders that they sought to build a permanent Chapel before they sought to build a permanent Dining Hall. Sir Arthur Blomfield was invited to prepare plans in June 1892, building began in spring 1893, the corner-stone was laid by Bishop Abraham on 15 June 1893 (which was Lyttelton's last day as Master), and the Chapel was consecrated on St Etheldreda's day (17 October 1895), by Archbishop Benson of Canterbury. By then the stalls were completed as seats, and included the impish carved heads of Lord Morley, Lord Salisbury, Sir William Harcourt, and other politicians prominent in the general election of 1895. But the stalls each side had no carved canopies above them, the windows had no stained glass, and the organ and sanctuary were 'temporary'.

The Chapel was an expensive undertaking for a college without means, and posterity is grateful that its makers built in faith for the future. Even so, the new Master, John Selwyn, who was the son of George Augustus Selwyn, and was invalided home after being the second Bishop of Melanesia in the Pacific, had to undertake a killing amount of begging to find the money. The original plan by Blomfield had to be narrowed by several feet to reduce the cost to an estimate of £8,000 for structure alone; the building may have lost something in proportion and perspective, and may have gained something in acoustic properties. John Selwyn himself gave (1896) the six stall canopies at the western end, and the rest of the western screen. In 1901 sixteen stall canopies were given, the two on the north-west and south-west corners by members of the College, the other fourteen by Cambridge residents as part of their memorial to Bishop John Selwyn. Even so, the Chapel still looked odd, with beautiful carved stalls up a quarter of its length, and brick walls partly covered with faded curtains for the rest. Old photographs of the Chapel almost always take it from the altar end, so that nothing but the end with carved woodwork is seen.

It was intended that all the windows of the Chapel should be coloured according to a plan. The College applied to Kempe, one of the finest Victorian workers in stained glass, who recommended single figures of saints in each panel, and not pictorial scenes running over the mullions. The great east window, by Kempe himself (dedicated 1902, partly paid for by subscriptions in New Zealand and Melanesia to commemorate George Augustus Selwyn), by any standards a fine work of art which has grown out of Selwyn itself, represented our Lord enthroned. It was agreed that down through each side of the Chapel should run saints and leaders of the Church through the centuries, until George Augustus Selwyn in the west window. The south-east window, in memory of Bishop John Selwyn, was dedicated in 1900; the half-window over the vestry in 1902, and three other windows in 1902-3, one to a scholar who died while an undergraduate, one to a Selwyn man killed in the Boer War, and the Boniface Anskar-Methodius window to Lyttelton. A point of argument was the inclusion of the Origen in one of the windows, a bold and deep thinker of the third century who was not regarded as a saint and was condemned as heretical by weighty Christian Councils. His inclusion was due to the third Master, A F Kirkpatrick, who in the academic side of his life did pioneering work in reconciling traditional divinity with the new knowledge of science and history. Then the windows stopped. The new taste of the twentieth century began to value light and air, and reacted against the atmosphere of Victorian glass. Probably taste will one day change again, and the old intention to make a historic series of Christian worthies will be revived.

It was intended that all the windows of the Chapel should be coloured according to a plan. The College applied to Kempe, one of the finest Victorian workers in stained glass, who recommended single figures of saints in each panel, and not pictorial scenes running over the mullions. The great east window, by Kempe himself (dedicated 1902, partly paid for by subscriptions in New Zealand and Melanesia to commemorate George Augustus Selwyn), by any standards a fine work of art which has grown out of Selwyn itself, represented our Lord enthroned. It was agreed that down through each side of the Chapel should run saints and leaders of the Church through the centuries, until George Augustus Selwyn in the west window. The south-east window, in memory of Bishop John Selwyn, was dedicated in 1900; the half-window over the vestry in 1902, and three other windows in 1902-3, one to a scholar who died while an undergraduate, one to a Selwyn man killed in the Boer War, and the Boniface Anskar-Methodius window to Lyttelton. A point of argument was the inclusion of the Origen in one of the windows, a bold and deep thinker of the third century who was not regarded as a saint and was condemned as heretical by weighty Christian Councils. His inclusion was due to the third Master, A F Kirkpatrick, who in the academic side of his life did pioneering work in reconciling traditional divinity with the new knowledge of science and history. Then the windows stopped. The new taste of the twentieth century began to value light and air, and reacted against the atmosphere of Victorian glass. Probably taste will one day change again, and the old intention to make a historic series of Christian worthies will be revived.

A second-hand Walker organ for the temporary Chapel was bought in 1891. It had a sweet tone and lasted, with grumblings, until 1939, when George Chase (Master 1933-45; portrait in Hall by Henry Carr 1946), gave a fine new Rushworth and Dreaper organ, incorporating parts of the old organ. This in its turn began to grumble, and in 1973-4, as a memorial to George Chase, it was replaced by a Harrison organ. It would be amusing to discover which bits survived from the late 1880s.

The paving of the sanctuary of the Chapel, and of the east wall, was part of the war memorial after the war of 1939-45. The memorial tablet and the sanctuary floor were dedicated by Chase (then Bishop of Ripon) in 1951, fourteen more stall canopies were dedicated by the Visitor (Archbishop Fisher) in 1952, and the remaining fourteen completing the woodwork of the Chapel, dedicated by Chase in 1953.

The east end was intended to have a reredos. Nikolaus Pevsner suggested that the altar and Kempe's noble window be linked by an ascending Christ, with black floating figures on the white wall, and recommended a Swedish artist, Karin Jonzen, for the work. The figures were dedicated by the Bishop of Ely on the eve of Ascension Day 1958.

Of the memorials in the Chapel, special mention must be made of the 'relics' of Bishop Patteson. George Augustus Selwyn fetched Patteson from England to work in the Pacific Islands. He became the first Bishop of Melanesia, and was murdered while trying to land on an island in 1871. His pectoral cross was given to John Selwyn who let it into the central place of the altar, and the College received his combined Bible and prayer book, which is on view in the Upper Chapel, together with a portrait. The College has always retained a connection with the diocese of Melanesia, and had, from its earliest years, a Patteson missionary studentship, held by several afterwards famous in Christian work overseas.

As in other colleges of Cambridge, undergraduates were required to attend so many 'chapels' a week – at first every morning and twice on Sundays. The Master used to make a regular report to the Council on their attendance, and on the too frequent rebukes which he needed to administer. Alec Vidler, while an undergraduate in 1920, led a little campaign for voluntary chapel. As in other colleges compulsion became less and less compulsory during the twenties, but the system did not end until 1935. Selwyn was not the last college to end it.

The ground slopes slightly from Grange Road towards the river. When the Chapel was built, it needed to be elevated on a 'causeway' to be level with the Tower and gateway, and this left a sunken centre of the court (as at Keble College), which was grassed over some three feet lower than the surrounding path, and with a gravel path across the centre from the gateway to the west door of Chapel. The ground took time to settle, and when piles were being driven for the university library in 1930 alarming cracks in the Chapel structure began to appear. Traces of these cracks may still be seen, e.g. over the south door of the Chapel. After the first movement, the ground remained firm, and though the College kept a look out when the Economics Building and Seeley Library were later built not far away, no further movement occurred.

The ground slopes slightly from Grange Road towards the river. When the Chapel was built, it needed to be elevated on a 'causeway' to be level with the Tower and gateway, and this left a sunken centre of the court (as at Keble College), which was grassed over some three feet lower than the surrounding path, and with a gravel path across the centre from the gateway to the west door of Chapel. The ground took time to settle, and when piles were being driven for the university library in 1930 alarming cracks in the Chapel structure began to appear. Traces of these cracks may still be seen, e.g. over the south door of the Chapel. After the first movement, the ground remained firm, and though the College kept a look out when the Economics Building and Seeley Library were later built not far away, no further movement occurred.

When the Chapel was built, the sunken Court was not yet beautiful, because it still contained the temporary Hall, Buttery, and (after the Chapel moved) Library. In 1898 the College laboured under a load of debt which made these temporary structures look too permanent. The debt was extinguished in 1901, chiefly with a gift from Bishop Edmund Hobhouse, one of Selwyn's old suffragans from New Zealand days, and the creator of the Patteson studentships. But without the aid of the Selwyn family and of the old Bishop's intimates, the College could hardly have survived.

There could have been no greater contrast than between the second Master, Bishop John Selwyn (1893-8) and the third, A F Kirkpatrick (1898-1907). Selwyn (posthumous portrait in Hall, from a photograph by Lowes Dickinson) was an ex-missionary and sea-faring man, who leaned out of his study window and shouted across the Court at undergraduates like a captain from his bridge. He had small use of his legs, and rode a tricycle round the town. As he could not easily stand he remained seated for the loyal toast. Senior members to this day remain seated for the loyal toast, out of no disrespect for the sovereign, but out of a custom of courtesy to a former Master. Kirkpatrick was an intellectual whose heavy beard (portrait in the Hall by C E Brock, 1908) was incongruous with his high falsetto voice. He was a scholar with an international reputation. But what the College needed was someone who would build a Hall and develop a Constitution.

The Hall

Richard Appleton, Fellow of Trinity College, was Master from 25 March 1907 until his sudden death, of influenza, on 1 March 1909. His initials and rebus (three apples and a tun) appear on the north wall of the Hall steps, and his portrait, painted posthumously from photographs and making him look younger than he looked to the College, hangs in the Hall. He was a man whom everyone liked. He instantly set out to raise money for a hall, and quickly got enough to start. The old Victorian plans by Sir Arthur Blomfield, who had died in 1899, were discarded, and the Council selected as architect the firm of Grayson and Ould, which meant chiefly Ould. At the east end, with the help of money from T. H. Orpen (formerly tutor, and a benefactor; portrait by C. E. Brock in New Senior Combination Room), they built quarters for the servants and the Bursary, at the west end (thanks to a gift from the widow of Bishop John Selwyn, who was specially munificent in these years) the Old Senior Combination Room and underneath a dining room for the College servants. The last dinner in the temporary hall was eaten by the 1909 candidates for entrance scholarships, the first dinner in the new hall at the beginning of the Easter term 1909.

Richard Appleton, Fellow of Trinity College, was Master from 25 March 1907 until his sudden death, of influenza, on 1 March 1909. His initials and rebus (three apples and a tun) appear on the north wall of the Hall steps, and his portrait, painted posthumously from photographs and making him look younger than he looked to the College, hangs in the Hall. He was a man whom everyone liked. He instantly set out to raise money for a hall, and quickly got enough to start. The old Victorian plans by Sir Arthur Blomfield, who had died in 1899, were discarded, and the Council selected as architect the firm of Grayson and Ould, which meant chiefly Ould. At the east end, with the help of money from T. H. Orpen (formerly tutor, and a benefactor; portrait by C. E. Brock in New Senior Combination Room), they built quarters for the servants and the Bursary, at the west end (thanks to a gift from the widow of Bishop John Selwyn, who was specially munificent in these years) the Old Senior Combination Room and underneath a dining room for the College servants. The last dinner in the temporary hall was eaten by the 1909 candidates for entrance scholarships, the first dinner in the new hall at the beginning of the Easter term 1909.

The initials of the then College officers are carved on the stone-work of the balustrade. Certain undergraduates illicitly carved their initials on a course of bricks near the north east angle. Among them is F.S.M. who was F. S. Marsh, later a Fellow, eminent Orientalist, and Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity, the first Selwyn man to be a Professor of the University. Marsh was the author of the former edition of this history, published 1944.

The Hall is a very satisfactory piece of architecture. Part of the woodwork is listed in the Cambridge Inventory of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (1959). It was always intended that the Hall should be panelled. The screen at the east end was made in 1909, at the cost of Prebendary William Selwyn. The woodwork of the west end comes from the altar panelling of the old English church at Rotterdam, built between 1699 and 1708 for the English community of merchants and traders. Queen Anne gave £500 to the building, the Duke of Marlborough contributed. The plan and ornaments came from the office of Sir Christopher Wren, possibly therefore being a design by Wren personally. In. 1913 the Rotterdam church was demolished. A. C. Benson, the Master of Magdalene, bought the woodwork and presented it to the College in memory of his father, the archbishop who dedicated the Chapel. The panelling down the sides of the Hall was not completed until 1922, and was made partly from wood of the Rotterdam church still unused, and partly from the vats of the derelict brewery of Magdalene College. Benson also presented to the library a letter from the diarist Samuel Pepys, in which he subscribes money to the building of the church at Rotterdam.

The 'old' Hall moved away from the Court, and can still be inspected as the Newnham Institute in Hardwick Street. That did not leave the Court beautiful, because it still contained the one-time Chapel, since 1895 used as the Library, and the earliest Senior Combination Room, which in 1909 was added to the Library.

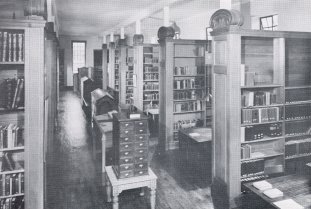

The Library

The war of 1914-18 came as a special crisis. 70 Selwyn men and two College servants were killed. The College barely managed to keep open, letting several staircases to the nurses of the Eastern General Hospital, and receiving only a trickle of undergraduates (1914; 29, including a future archbishop; 1915, 11; 1916, 2; 1917, 3, including another future archbishop). In 1916 the terminal fee was raised for the first time since the foundation; from £27 to £28; in 1918 to £33. The lawn of the College garden spent the war years as a vegetable allotment, the lawn of the Court was allowed to grow for hay. Chickens were bred behind the north range.

The war of 1914-18 came as a special crisis. 70 Selwyn men and two College servants were killed. The College barely managed to keep open, letting several staircases to the nurses of the Eastern General Hospital, and receiving only a trickle of undergraduates (1914; 29, including a future archbishop; 1915, 11; 1916, 2; 1917, 3, including another future archbishop). In 1916 the terminal fee was raised for the first time since the foundation; from £27 to £28; in 1918 to £33. The lawn of the College garden spent the war years as a vegetable allotment, the lawn of the Court was allowed to grow for hay. Chickens were bred behind the north range.

When after the war the junior members were consulted on what they would like for a war memorial apart from the memorial tablet in the Chapel, they looked with distaste at the 'temporary' library still ruining the Court, and said that they would like a Library. The former temporary Chapel had been very necessary as a Library; for though the College could not then afford to buy many books – so late as 1914 its annual grant to the library was £20 – it received two splendid benefactions, from Canon William Cooke (1894) and Edward Wheatley-Balme (1896), which could certainly not have been crammed into the old Tower Room. These bequests gave the College not only an excellent working library, but some books of such value and rarity as to astonish eminent bibliographers, who came on routine inspection expecting to despise and departed in humility. They also made it impossible to destroy the Court's surviving disfigurement.

T. H. Lyon was chosen as the architect, and drafted plans for a Library in the garden, almost closing the gap between the Chapel and F staircase. It would have been a noble Library. But the College reckoned neither with the increase in building costs after the war, nor with their difficulty in collecting money. At last they told Lyon that they could not build his design, and asked him to design the Library, as it now stands, at a cost of £4,000. It was finished by the end of 1929. The bridge connecting the upper floor of the library with C staircase was given by two Japanese noblemen in gratitude for hospitality at the Master's Lodge. The 'swastika' above the arch on the west side is the cognizance of the family of one of them, the Marquis Tokugawa. The 'temporary' Library may now be seen as part of an engineering workshop in King's Road.

So at last the Court was cleared, and fair it looked. T.H. Lyon also designed the railings which join the Chapel and F staircase (erected 1932), and the wall between the Chapel and the Master's Lodge, built in 1935. He intended the niche for a statue but no one could ever think what statue.

In two respects the Court of 1936 differed from the Court of 1973. Between the Senior Combination Room and A staircase, where are the new J.C.R. and new S.C.R., was an open space, where a high impenetrable holly hedge divided the garden of Selwyn Close from the Court, and a few dilapidated geraniums tried vainly to add a little colour. Secondly, the Court was sunken. Men looked at it and loved it because they compared it with their memory of builders' litter. But those who had never known the builders' litter were not sure about it. It made the tall buildings from A to F look as though they were one storey higher. Some people began to wonder if the Court would not look better filled in. The point seemed academic, because no one could imagine the College ever paying for so aesthetic a refinement.

Early in 1961 Sindall's, who were building both the new telephone exchange in Long Road and the Harvey Court of Caius in West Road, could not think what to do with the excellent soil which they must remove. They suddenly offered to fill and level the Court at their own expense. The Fellowship consulted architects who were unanimous in urging them to go ahead. So they agreed, with one vote cast against. Sindall's said that they could do it in five days, but reckoned without the soil and without the difficulty of getting lorries into the court, and the first weeks of Easter term 1961 were hideous with the noise of bulldozers. The undergraduates did not approve of the decision. They built a gravestone with flowers to the memory of a beautiful lawn. Many old Selwyn men who returned to the College did not notice any change.

The Constitution

The College was intended by its founders to be a College of the University like any other college (the Charter describes Selwyn as 'a College at Cambridge') but with its own special traditions in religion and in simplicity. But when the College was actually founded it was seen to differ from the other colleges, because (i) The Governing Body was a Council of persons outside the College, (ii) there were no Fellowships, (iii) there were no endowments, (iv) the College was regarded as a 'denominational' College; and though nothing in the university statutes or the law of the land prevented the university from having purely denominational colleges as full colleges equal to the others. The university had a reluctance to accept the principle of such a college. It was not so much that the Charter required the Master to be in holy orders, for St. Catharine's College was still then required to have a Master in holy orders. It was that the founders talked as though they intended all members of the College to be members of the Church of England. In any case the university is not accustomed to recognise new institutions as full colleges until it is sure that they are viable financially.

The university therefore recognised Selwyn as a Public Hostel. This form of recognition meant that the Master would not be Vice-Chancellor, that the College could not appoint proctors, that the College did not pay tax to the university on its income, and that it could not put undergraduates in lodgings. But the College had no desire to appoint proctors, could not have afforded to have its Master Vice-Chancellor, and had no income on which to pay tax. In every other way it was a college of the university, matriculating men, teaching them, awarding them prizes and scholarships, entering them for examinations, presenting them for degrees, encouraging them up the river or down the football field. There was small disadvantage that was tangible. But a soreness in feeling may be a disadvantage. 'Hostel' somehow seemed an opprobrious name. It rankled, much more with the teaching staff than with the undergraduates, that a man who appeared in the Senate House had H. Selw. after his name. 'Hostel' suggested that Selwyn existed only to provide board and lodging. The struggle to become 'a college' seemed but half done.

This feeling grew because the teaching staff were not Fellows. The founders, seeing that the task of getting the College on its feet would need toughness, gave autocratic powers to the Master. The college lecturers and teachers bore the same relation to the Master as assistant masters to the headmaster of a school.

The Council, which was the governing body, was a group of eminent outsiders, including under the Charter certain outsiders ex officio, like the Bishop of Ely or the Dean of Lichfield. This worked under Lyttelton, and well under J. R. Selwyn, partly because the teaching staff was few in number, partly because the two Masters treated the lecturers as colleagues and not as assistants. But, as the teaching staff grew in number and weight, this difference between their own terms of service and those of the senior members in any other college became a sore. Several of them thought that they knew better than Kirkpatrick what was good for the College, and they may have been right.

In 1903 it was proposed to have Fellows, but the proposal failed chiefly because the Master (Kirkpatrick) disapproved of it. The proposal reappeared in June 1910, when J O F Murray, Appleton's successor, was Master (portrait in the Hall by Kenneth Green, 1928). The proposal got a fair wind, new statutes were written and obtained the assent of the Visitor, and on 7 October 1913, three days after the new statutes were finally sealed, the Council elected the first five Fellows of Selwyn College: H C Knott (mathematics, tutor, praelector, bursar; portrait in the new SCR by Kenneth Green; clock above the Hall given by his widow 1928) W E Jordan (history and classics, tutor), L A Borradaile (natural sciences, dean; the old servants' dining room was turned into a public room and called after him, 1958), S C Carpenter (theology, tutor, precentor) and W Nalder Williams (classics, law). The statutes created an Administrative Body, that is the Master and Fellows, to which the Council handed over all the domestic and academic arrangements of the College. The Council continued to elect Fellows, but did so on the nomination of the Administrative Body.

The title of Fellow carried one other meaning. The 1913 statutes introduced for the first time the word 'research'. In early years a mood existed which supposed that the object of the College was to get undergraduates through examinations cheaply, without putting them to the expense of hiring a private coach. They were not supposed to be much concerned with learning for its own sake; even though the College teaching staff already included men afterwards famous in the world of scholarship. The 1913 statutes recognised the change of mood.

A tribute must be paid here to the generation of Fellows who administered Selwyn between the wars. Their stipends were not much better than those of the original College officers, but their primary interest in their University life was "the College", to which they orientated their work and their leisure, and in many cases their benefactions. Without this devotion Selwyn could not have become a full College as early as it did.

The Statutes of 1913 created a constitution which could only be temporary. The Master and Council of outsiders controlled the policy, the Master and Fellows administered affairs. The situation could hardly last. Sooner or later the two bodies were likely to merge, and the Master and Fellows must become the Council. In 1924 the Council consciously began to take the step of electing the Fellows, one by one, to be members of the Council. As this process went on, the obvious end must be the disappearance of the Council. In the way of turning the Fellows into the Council stood two difficulties, one legal and one religious.

In 1923 a Royal Commission recommended reforms to the university, and in 1926 a second Royal Commission incorporated these recommendations into new university statutes, and into certain new statutes for the colleges. The university statutes of 1926 abolished the old 'Public Hostel' status; but the university had already ceased, in June 1924, to put the prickling H. before Selw. in public documents. The College became an 'Approved Foundation' of the university – more a change of title than a change of reality, but very acceptable to the resident members. The university could no longer withdraw its recognition of the College without changing its own statutes – in the circumstances an unthinkable operation. Selwyn was included under the provisions of the Oxford and Cambridge Act 1923, which made it possible to vary the content of the Charter by introducing the appropriate provisions into the College statutes. This meant that it was later possible to remove the ex officio members from the Council and leave the Fellows as the Council. It would be wrong to regard the old Council as just a nuisance in the government of the College. Its members were wise and liberal-minded men who gave generously of their time, labours and money for three-quarters of a century. They should be remembered as benefactors who successfully guided the College through its early and difficult years.

The religious difficulty was more perplexing. The Charter laid it down only that the College should aim at education according to the principles of the Church of England. It was nowhere stated that members of the College must be members of the Church of England, and from the first it was recognized that the Master had a right to admit undergraduates who were not. This discretion applied also to those who won scholarships or exhibitions. Nothing said that the Fellows, other than the Master, must be members of the Church of England, because there were no Fellows. Dissenters were however expected to attend compulsory chapel like other members of the College. And certainly, for decades, the administrative practice was to expect applicants to be members of the Church of England, and even until 1956 other admissions were regarded as the exceptions.

When in 1913 the first statutes were drawn up, it was there provided that the statutes should make it clear that scholars as well as Fellows, i.e. all receiving payments from the endowment, were members of the Church of England. Thus the 1913 statutes limited the terms of the Charter.

The Council of outsiders had been erected by Charter partly in order to maintain the religious tradition. In moving towards the transformation of the Council, sensible on every constitutional ground, the Fellows were much concerned on the way in which the tradition was to be maintained. They were under the chairmanship of William Telfer (Master 1945-56, drawing by H A Freeth in Old SCR, 1956) with A C Blyth as the Vice-Master (drawing by H A Freeth in Old S.C.R., 1957). But much of the detailed work was done by P J Durrant (Fellow from 1923; afterwards Senior Tutor and Vice-Master; portrait 1966 by Davidson-Houston in New SCR, drawing 1966 by Freeth in Old SCR). The Fellows consciously returned to the position as it existed before 1913, where, as with undergraduates generally, there was no bar to scholars or Fellows who were not members of the Church of England. But they were very ready, and indeed eager, to accept the responsibility for maintaining the religious tradition and keeping faith with the trust as it had been designed. They had received a religious tradition of breadth, and they would interpret it with tolerance and charity. The Charter was printed with the new statutes of 1957 and remains in force so far as not varied by those statutes. The new statutes also made it possible, in certain circumstances, to have a layman as Master.

These statutes opened the way for recognition as a college by the university. This passed the Regent House of the university easily and without argument, and was approved by the Queen in Council on 14 March 1958.

Internally the College was little affected by the change, as it had been doing the work of a full college for nearly 80 years. But it made a difference to the feelings of the Fellows, especially the older Fellows whose memory went back to the days when the College was suspect in the university. And it made a great difference to the demands of the university upon its senior members. Henceforth more of them served as members or chairmen of weighty university committees. The first year the College had a Vice-Chancellor was in 1969-70. The first time it nominated a senior proctor of the university was the year 1969-70.

Post-war Growth

After the war of 1939-45 all universities were transformed by the new law on education. Not only did those whose education was delayed by war wish to come up simultaneously. Grants made it possible for anyone who could get himself accepted to come up. Hence the pressure for entry with which that age became familiar. Selwyn was transformed as rapidly as any college. Like other colleges it expanded to meet a national need, and then found not only that the national need persisted but that finance demanded the larger numbers of fee-paying students. In 1938 the number of junior members was 165, of whom 133 were in College and 32 in lodgings (lodgings were not permitted to Selwyn while it was a Public Hostel; the rule was first relaxed after the first World War; all restrictions were removed 1936); in 1948 the number was 280 (137 in College, 39 in houses nearby which the College bought, and 104 in lodgings).

During the war of 1939-45 the RAF occupied alternate staircases for cadets of an Initial Training Wing. The cadets were drilled on the paths of the court, and so damaged them that the Government paved them with asphalt at the end of the war. The Porters' Lodge was equipped as an air-raid warden's post, manned 24 hours a day, mostly by a Fellow or senior member of the College staff. The warning siren for West Cambridge was on top of the tower. In 1940 lawns of the garden were covered by large dumps of coke as a fuel reserve. These so poisoned the ground that it was two or three years before the grass would grow again.

Government grants had an instant effect upon the tradition of simplicity. The College could no longer fulfil its purpose of bringing to the university men who could not afford it since everyone could now afford it. Nor was it possible in the circumstances to keep the fees below the level of fees at all other colleges. Hence activities became possible for Selwyn undergraduates which a previous generation preferred to avoid on grounds of extravagance. The first May Ball in the history of the College was held in 1948.

The new numbers of undergraduates meant a corresponding increase in the number of Fellows (1939, 10, 1973, 35). The Old JCR and the Old SCR became simultaneously too small. In 1964 the gap between the SCR and A staircase, which was still the holly hedge and sad geraniums, was replaced by a new building (architect, Johnson-Marshall, whose main instructions were that he could be as modern as he liked, provide he harmonised it with the existing Court), having the JCR on the ground floor, the New SCR on the first floor and two Fellows' sets above. The JCR at the bottom of C staircase became, for a time, two sets of rooms, but was soon handed back to the JCR for the purposes of television. The number of scholars, and of first classes in triposes increased.

Housing the new numbers meant unsatisfactory lodgings, and the quest for money to build a new court began. The College had acquired from Caius College the freeholds of all the houses between its northern boundary and West Road, but several of the leases had many years to run, and as a whole the area was not available for building. For a time the College expected to build its new Court in the garden, and a dramatic plan was offered to that end. Finally, the Fellows felt that they could not destroy the garden; and when enough space was afforded by the purchase of the leaseholds of three houses across the road, and Jesus College was kind in selling the freeholds, they determined to build a new Court there. Old members of the College were again generous in response to an appeal, and when the Cripps foundation stepped in with a munificent gift, the success of the new Court was assured. 'Cripps Court', as it was at once named, was formally opened by Mr Humphrey Cripps on 17 May 1969 but had undergraduates and graduates residing from the previous October. Part of the building was set aside for graduates and research students. The architect was Gordon Woollatt of Nottingham. Cripps Court made it possible to bring everyone back into College accommodation; and so helped to preserve that particular sense of community which from the foundation was a special feature of the College.

Housing the new numbers meant unsatisfactory lodgings, and the quest for money to build a new court began. The College had acquired from Caius College the freeholds of all the houses between its northern boundary and West Road, but several of the leases had many years to run, and as a whole the area was not available for building. For a time the College expected to build its new Court in the garden, and a dramatic plan was offered to that end. Finally, the Fellows felt that they could not destroy the garden; and when enough space was afforded by the purchase of the leaseholds of three houses across the road, and Jesus College was kind in selling the freeholds, they determined to build a new Court there. Old members of the College were again generous in response to an appeal, and when the Cripps foundation stepped in with a munificent gift, the success of the new Court was assured. 'Cripps Court', as it was at once named, was formally opened by Mr Humphrey Cripps on 17 May 1969 but had undergraduates and graduates residing from the previous October. Part of the building was set aside for graduates and research students. The architect was Gordon Woollatt of Nottingham. Cripps Court made it possible to bring everyone back into College accommodation; and so helped to preserve that particular sense of community which from the foundation was a special feature of the College.

This building was but one of several college or university buildings new after 1960. The university expanded westward and so (especially from 1961, when the Economics building at the end of the garden was finished, as the first of a series of arts faculty buildings) altogether removed that sense of geographical isolation which had been at once a strength and a weakness of the early College.

The Boat-house

In 1883 the College rented the old boat-house of the town rowing club. It was a marvellous structure to look upon, with a verandah and interesting architecture of wood and corrugated iron. It had two demerits – you could not get near it except on foot or by river and therefore supplies were difficult and repairs costly; and it was always on the point of falling down. Never in all history has a college possessed (for it bought it in 1928) so ramshackle a building. From this unique base the undergraduates developed a fine tradition of rowing; rising to second in the Lents in 1934, third in the Mays 1931, supplying blues to the University boat and men to row in the Olympic Games. Architects kept uttering dismal warnings, and crews continued to thrive. The squalor became unbelievable, and still was beloved. Finally the College, which received a bequest from Mrs Page for the boat club, joined with King's and Churchill and the Leys School in a new boathouse further away (opened 1968), and sold the most remarkable building in Cambridge.

The Playing Field

In 1883 Selwyn leased from King's the playing field which is now the City's rugby pitch on Grantchester Road. It was conveniently near, but in those days full of tussocks, and liable to be water-logged in winter and cracked in dry summers. In 1937 the College bought the Clare half of the 13 1/2 acre field on Barton Road hitherto shared by King's and Clare. It raised money for the purpose, partly by selling the old Selwyn postage stamps, one of a number used by colleges in a College post during the 1880s, until the Postmaster General stamped on the practice in 1986. (The stamp had the College arms on it). The dividing line between the King's half and the Selwyn half of this field runs from north to south through the centre of the ground. The pavilion was built by King's as a war memorial of the 1939-45 war, and opened in 1957. Games have gone up and down; in the middle fifties the College was distinguished at hockey; in 1970-73 the Rugby XV played in three rugby finals within four years, winning two of them.

The College Staff

In the early days teenage servants lived in College, high up on C or D staircases. They were made to attend Compline every day at 10 p.m. and disliked it more than the undergraduates disliked their compulsory chapels. On Sundays there was a service for the staff an hour before the service for the rest of the College. Soon the Selwyn staff were famous for their athletic prowess, in the days when competition between the 'college servants' clubs' was keen and of a high standard. What is now Selwyn Close was originally called 'The Cottage' and was built (1884) for the head College servant, known at first as the Steward; his successor, called the Butler, lived in College, at the top of F staircase, as a bachelor; and meanwhile dons moved into Selwyn Close and called it (1913) by that name. Then the White Cottage (architect T H Lyon) was built for the head College servant now under the third name of Manciple. The College staff always felt a part of the College community, and some of its members had extraordinary lengths of service. The record was held by Sydney Frost, 1903-64. Among College benefactors no longer living might be recorded (the list is far from exhaustive) the names of William Dempster (1882-1910), first senior servant; Henry Chapman (1882-1931), butler; David Heffer 1892-19 30) head porter; Bill Phillips (1882-1925) boatman; Alf Woodhead (1918-1968) bicycle man and general handyman.

Members of a college look back upon their institution variously, but often with affection; whether for the opening of their minds, or the new consciousness of a vocation, or the making of friendships, or the memory of enjoyable days.

An institution can never fulfil precisely the intentions or expectations of its founders because it is set in history, and needs to adapt and adjust to new generations and circumstances which its founders could not foresee, while it seeks still to follow the main aims of the foundation and the trusts which it has inherited. No doubt the decades of struggle to establish the College in buildings, money and repute, rather helped than hindered that sense of community which has marked the society. It elicited argument and sometimes controversy but, much more, generosity and even self-sacrifice. Not from the first day in 1882 could it fulfil all the hopes of its more sanguine parents. But it could always try to fulfil them, and there has never been a moment when it ceased to try. The founders wanted a community where religion, sane and tolerant but not lukewarm, was practised; where men respected simplicity of life and of character more than their opposites; where those who did not all come from well-to-do homes could receive what a university has to offer; and where the members pursued what the founders called (though we would not) "high culture of the mind"; that is, the College should be a community of people who think, and study, and seek to diminish the ignorance both of themselves and of the world. No present member of the College can look back upon what was done to these ends by the successive generations of Fellows and junior members and servants, without a sense of gratitude.