The new Pope watched the film Conclave. Based on Robert Harris’ (SE 1975) book, Conclave was a guide to the mysterious

Vatican processes that elect the global leader of the Catholic Church. Robert, one of Britain’s most successful novelists, talks with Roger Mosey about the construction of the story, his relationship with faith — and how the transformative power of Cambridge is changing.

Robert Harris attends the Conclave Headline Gala during the 68th BFI London Film Festival in October 2024.

Robert Harris didn’t go to the Academy Awards ceremony at which Conclave won the Oscar for best adapted screenplay. “I wasn’t invited, to be honest, but even if I had been invited I wouldn’t have gone. That would have been my idea of hell. I’d sooner be in a good Cambridge pub than in Los Angeles.”

Robert was briefly seen on stage at the Bafta ceremony in London a few weeks earlier, on a night which marked the scale of success of his novel and the resulting movie. Conclave was hailed as the Best Film, as well as being named Outstanding British Film, and winning again in the best adapted screenplay category. But the event still wasn’t for him. Talking to me via Zoom from his home in Berkshire, he is emphatic that is where he’d rather be: “I’m a novelist or writer by temperament as well as by profession. I like being alone in my study, working quietly. I don’t like all the hullabaloo.”

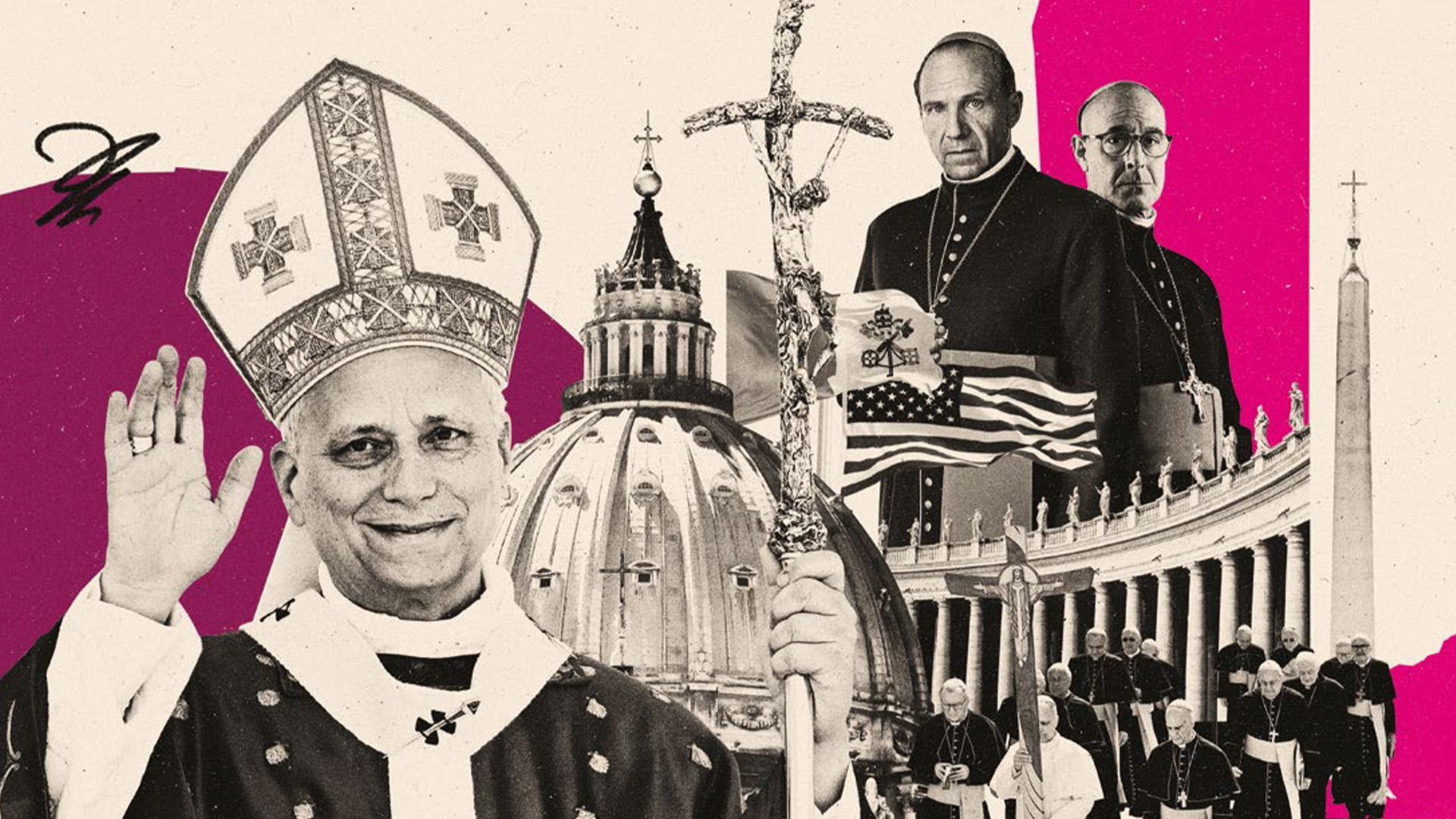

Yet he enjoys the influence that his writing has. The election of a new pope is always a huge global story; and, as Pope Leo XIV emerged as the new leader of the Catholic Church, for millions of people it was the fictional world of Harris’ conclave that shaped their understanding of what was going on in the Vatican. And it wasn’t just the public: the new pope, and other cardinals, had seen the film too. The pope’s brother John Prevost told American television about their family conversation: “I said, ‘are you ready for this? Did you watch Conclave, so you know how to behave? And he had just finished watching the movie.” When Robert received his CBE at Buckingham Palace, the King revealed himself as another Conclave viewer.

A man watches the film Conclave on his laptop as he waits near the Vatican to attend late Pope Francis' funeral in Rome in April 2025.

Harris attributes part of the success to the crafting of the project. “They recreated the Sistine Chapel and completely took you inside it. It just shows what you can do with $20 million and very good actors.” It is the process and the interplay between the cardinals that intrigued him. “They’re locked away. They have nothing to do but concentrate on the matter at hand. You see the strengths and weaknesses of the candidates, and you coalesce around an agreed individual. And it seems to work pretty well.”

There is a timely echo here of the process for electing heads of house in Cambridge colleges, and Harris says he was influenced by the C.P. Snow novel The Masters, set in the 1930s. “I always thought it was a very good novel about politics, and a conclave is even more an exercise in politics on a vast scale. But they’re both about people locked in, having to reach a conclusion and having to enter a two-thirds majority with endless secret ballots until they get there. It’s a perfect dramatic device, like a reading of a will.”

At this point, we agree that the electors at Selwyn – many of whom saw the movie during the recent contest for the mastership — were probably allowed into the outside world to have dinner, at least. And certainly to have a break over Christmas. But Robert sees further parallels: “Broadly, every institution — whether a Cambridge college or a political party — is split between progressives and conservatives, and the church is no different.”

We must be careful about spoilers here, but Conclave has a twist in its outcome which the church and no Cambridge college has yet managed. (So far as we know.) I suggested to Robert that the revelation was easier to deliver in the film, with the help of casting, than it was in the book. “Yes, I conceived the twist from the outset. I hope it played into the themes of the novel, and it wasn’t just for the shock value. In preparation for writing the novel, I read the gospels end to end, over the course of a day or so, almost as if they were themselves a novel. And I was bowled over by them: I was struck by the overwhelming force of the message of Christ, and its revolutionary power. About poverty and the disgrace of being rich and welcoming strangers and pacificism. I compared this revolutionary message to the great edifice of the church which seemed to encase it and make it safe: "I wanted to find some way of suggesting a pope who would subvert all this.”

I have interviewed Robert Harris more times than any other guest at our Selwyn events and webinars, and like thousands of alumni I have read most if not all of his books. But in his amiable straightforwardness, it is tricky to work out what he believes personally or which characters win his sympathies. It’s all deliberate, he says. “One of the things I love about being a novelist of my particular kind is that I never write about myself. The joy is the imaginative empathy of trying to inhabit a character.”

But there is, he concedes, something of himself lurking within Conclave. “I am full of doubts. I lack certainty, and I transpose a lot of that. A great mentor of mine was Anthony Howard, who wrote the official biography of Cardinal Basil Hume. At the end of his life, Cardinal Hume had doubts, and I wanted to write about someone hugely senior in the church who nevertheless starts to wonder if God is there. So, in the novel, the dean of the college of cardinals makes a speech about the great enemy of tolerance being certainty, and certainty being the enemy of faith — and that is very much from the heart. One of the things I love about the film is that the whole speech is transposed from the book. It’s the nearest I’ve come to a statement of my own philosophy.”

So what next for Harris? “I think I’m going to do another Roman novel,” he says, noting that his Cicero trilogy involved an enormous amount of research — “a pleasure for me” — and it is likely to span 30 years and include “quite a lot of military stuff”. Which raises the question of how much his time at Selwyn influenced this attitude to research, and how much the college shaped him. “I was no great scholar,” he concedes, “but I did spend three years studying English academically and that was incredibly useful. That has made me and the books. They are a reflection of my education.” But simply being at Cambridge was transformative. “I came for my interview when I was 17 from a state school. No one had been to university from my family. And I had the most marvellous time: it moulded me and gave me a lot of confidence.”

We have discussed over the years our similar experiences, albeit with mine being at Oxford. It leads to a conclusion that he expresses with an uncharacteristic tinge of regret. “Looking back, I’m like you. We’re children of a particular post-war inheritance — an establishment, following the path that led from an ordinary home into Oxbridge, into the BBC, and into the cultural establishment, if you want to call it that. I don’t know that the path is so clear anymore. I feel very much a product of a world that’s gone or going."